Excursion to Buru

The first stop where Markus Mailopu accompanied the II. Freiburg Moluccan Expedition—Karl Deninger and Erwin Stresemann to be precise, as Odo Deodatus I. Tauern had already left the expedition at this point—was the island of Buru, not far from his home Seram. Markus Mailopu spent three months on Buru until he traveled to Germany together with Deninger and Stresemann.

On Buru, Markus Mailopu had a significant influence on the success of the expedition: He was in close contact with the local population, helped with the surveying work and contributed significantly to the exploration of the routes. The following storymap shows the course of his route and his contribution to the success of the expedition. Move the cursor over the map to see the individual stops.

Markus Mailopu's route on Buru

The content of the visualization orginates form the following sources:

Emge, Andus. Erwin Stresemann: Tagebücher, Berichte und Briefwechsel der II. Freiburger Molukken-Expedition 1990-1912. Singapur, Bali und die Molukkeninseln Ceram und Buru. Bonn, 2004.;

Stresemann, Erwin. Die Paulohisprache: Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Amboinischen Sprachengruppe. M. Nijhoff: 's-Gravenhage, 1918.;

Wanner, Johann. "Geologische Ergebnisse der Reisen K. Deninger's in den Molukken, I. Beiträge zur Geologie der Insel Buru", in Beiträge zur Geologie von Niederländisch-Indien, Abt. III, Absch. 3, 1922, p. 59-112.

Two stops in focus: Lake Wakolo & Gunung Kapalatmada

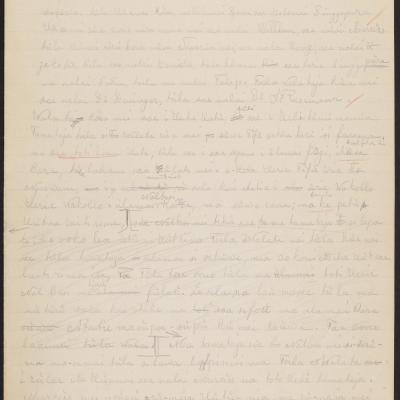

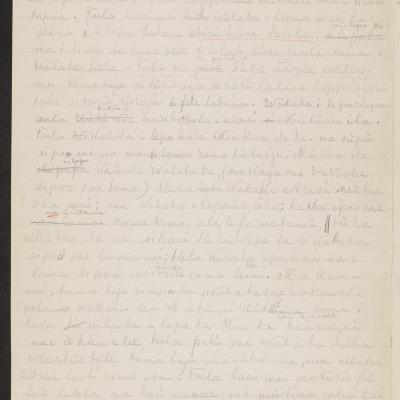

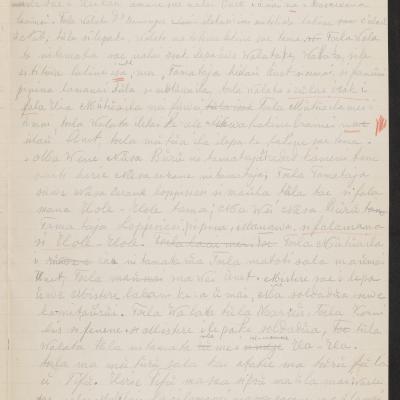

The following section takes a closer look at two excursions in which Markus Mailopu participated and contributed to their success. The descriptions are primarily based on Markus Mailopu's text "From the mountain Kapala Madang on the island of Buru" (Paulohi: Herie ulate kapala Madan sue nusa Buru; German: Vom Berge Kapala Madang auf der Insel Buru), in which he gives an overview of his time and experiences on Buru. The text can be read in Stresemann's publication “Die Paulohisprache: Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Amboinischen Sprachengruppe” 1 and Markus Mailopu's "Paulohi manuscript". Stresemann's book contains four texts of the "Paulohi manuscript", which Stresemann transcribed, edited, translated and published as Paulohi speech samples in his book. In addition to Markus Mailopu's texts, Stresemann's records were also a valuable source for the descriptions.2

Lake Wakolo: Mediating between locals and foreigners

In the first few days on Buru, Markus Mailopu accompanied Erwin Stresemann to Lake Wakolo, where they dedicated their time to survey the lake. During their stay at the lake, Mailopu and Stresemann were dependent on local support. For instance, they required porters, a boat and oars to explore the lake, as well as guidance through the terrain. However, both Stresemann's and Mailopu's reports reveal, the local communities' reluctance and fear, which complicated the expedition's work. In his text, Markus Mailopu describes his arrival and the encounter with the local community in Nalbessi as follows:

Mailopu's account suggests a rather positive interaction, while a different picture emerges from Stresemann's diary. He reports on Mailopu's search for carriers on another day, during which the recruited individuals did not seem to have followed him entirely voluntarily. Nevertheless, both accounts illustrate that Mailopu was in close contact with the local community during his time on Buru—as they were essential to the success of the expedition—and contributed through his interaction to the success of the excursion to Lake Wakolo.

Not only did the search for porters pose a challenge, but finding a boat that was necessary for surveying the lake also proved difficult. Once they finally got hold of a boat, Stresemann and Mailopu were able to begin surveying the lake, about which Mailopu reports the following:

Mailopu and Stresemann thus reached a very different conclusion than their predecessors, thereby contributing to the island’s topographic exploration—an undertaking that, given the complexity of the measurements, was easier to manage together.

Gunung Kapalatmada: Path-making to the summit

During their stay on Buru, the expedition team wanted to climb the island's highest mountain, Gunung Kapalatmada, which at that time was known was Kapala Madan or Kapla Madang. However, this proved to be a major challenge as the ascent was much more difficult than anticipated. After several unsuccessful attempts to find a suitable path to the summit, the group—consisting of Mailopu, Deninger, and several interlocutors—began their descent back to the coast. After meeting Stresemann and his team along the way, they joined the group and together they returned to the camp at the foot of the mountain. They stayed there for some time before making a second attempt to climb the summit. Mailopu's report serves as a testimony to his impressive achievement, as he was the one to identify a pathway to the summit:

After the demanding but successful ascent of the mountain, the team returned to their camp at the foot of the mountain. The next day, the group set off again for the summit—this time with plenty of equipment, as Mailopus's report shows once again:

In the end, it is largely due to Markus Mailopu's—and the other interlocutors'—effort that the expedition was able to climb the summit which certainly also contributed to a better understanding of the topography of the island.

Hand-drawn map of Buru – The topographical findings of the expedition summarized in one image

The expedition team devoted a large part of their time to surveying the island's topography, to which Mailopu also contributed. During their stay, a folding map of Buru from 1910 served as a basis for orientation on the island for the expedition team. However, hand-drawn markings on the map show that the team had come to different conclusions and did not agree with the existing map in all aspects. They summarized their findings in a hand-drawn map, which they must have created during or after their stay.

Today, this map is an informative historical document that, thanks to its markings, provides insight into the stops and route of the expedition. Move your cursor over the image to learn more about them.

___________________

References

- Stresemann, Erwin. Die Paulohisprache: Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Amboinischen Sprachengruppe. 's-Gravenhage: M. Nijhoff, 1918. (English: The Paulohi Language: A Contribution to the Knowledge of the Amboinese Language Group) ↩︎

- Stresemann's diaries and correspondence concerning the expedition, as well as the official reports, were collected and transcribed by Andus Emge. He published his findings in 2004 under the title "Erwin Stresemann: Tagebücher, Berichte und Briefwechsel der II. Freiburger Molukken-Expedition 1990-1912. Singapur, Bali und die Molukkeninseln Ceram und Buru". This publication provides a systematic yet personal insight into everyday life on the expedition.↩︎

- Stresemann, Erwin. Die Paulohisprache: Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Amboinischen Sprachengruppe. 's-Gravenhage: M. Nijhoff, 1918, p.228. Original in German.↩︎

- A fathom is a historical, region-specific unit of length, volume, and area—in this case, a maritime unit of depth (Source: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klafter). Depending on the region, 1 fathom corresponds to between 1.62 m and 1.88 m (Source: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nautischer_Faden). The previous survey of the lake therefore yielded a depth of between 243 m and 282 m. According to current knowledge, the lake has a depth of 174 m (Source: https://id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Danau_Rana).↩︎

- Stresemann, Erwin. Die Paulohisprache: Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Amboinischen Sprachengruppe. 's-Gravenhage: M. Nijhoff, 1918, p. 228. Original in German.↩︎

- ibid., p. 230 f. Original in German. ↩︎

- ibid., p. 231 f. Original in German. ↩︎