Visiting Europe

After Markus Mailopu had already worked with the expedition members on Seram and Buru for several months, he decided to travel with Erwin Stresemann and Karl Deninger to Germany—more specifically Freiburg. The exact circumstances surrounding this decision are unknown today. Stresemann only wrote that Mailopu had chosen to accompany them for a period of one year.1 The trip to Europe lasted over a month and a half, taking them from Maluku to Singapore and then through the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean. There, the group disembarked in Genoa and traveled on to Freiburg—Mailopu's new home for the following year.

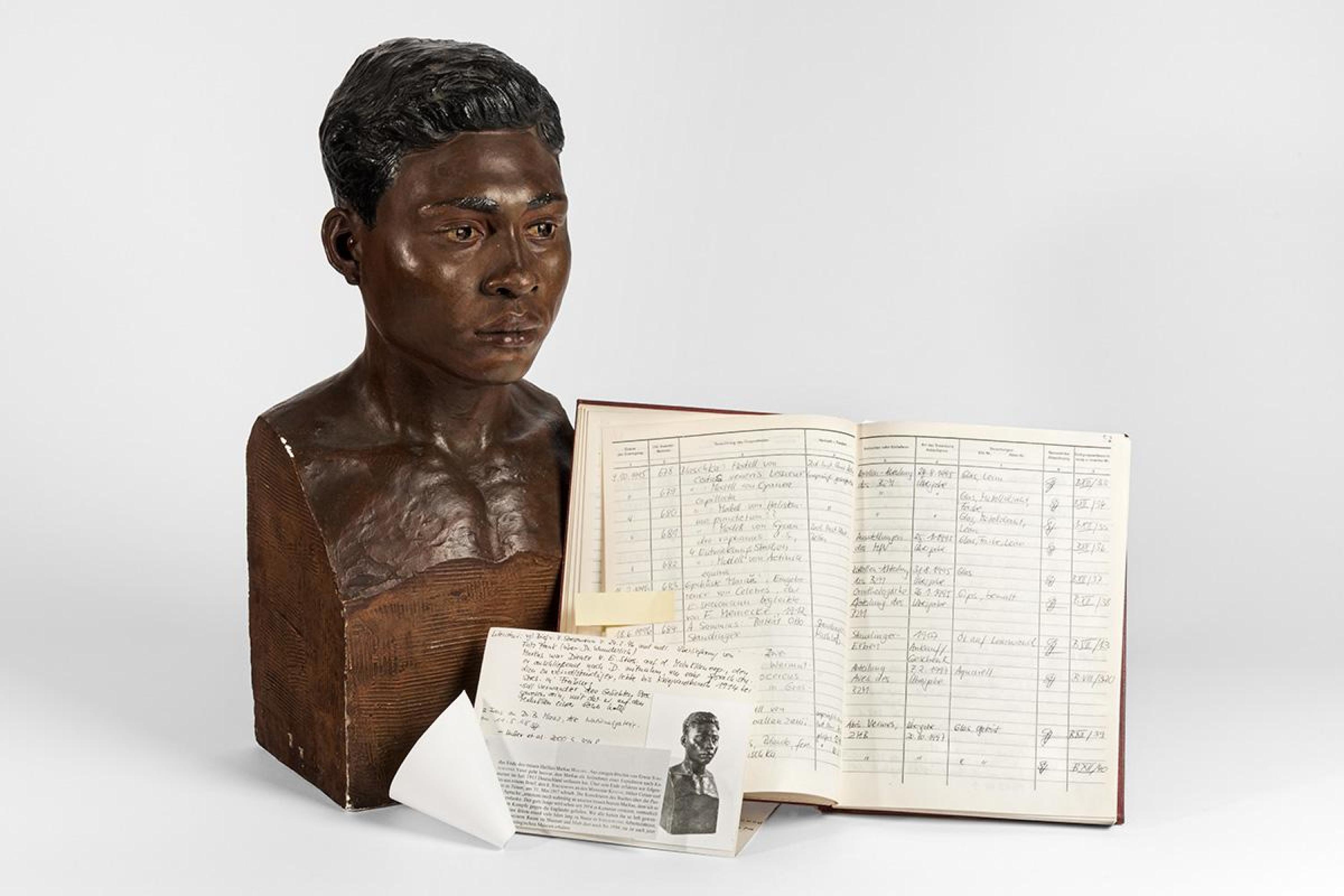

This bust is a remarkable indicator of the complex relationship that continued to develop between Markus Mailopu and Erwin Stresemann after their arrival in Germany. The piece was displayed in Stresemann’s private house until it was moved to his office desk at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin. Once asked about the bust by a student, Stresemann is said to have replied: “This is my friend, Markus Mailopu from Seram”.2 Yet, Stresemann did not commission just any sculptor but Friedrich Meinecke from Freiburg. Meinecke had produced several works for Freiburg’s public spaces, but he was equally renowned for his ethnographic sculptures which were exhibited in museums across Germany.3 It is reasonable to assume that Stresemann chose Meinecke precisely because of the sculptor’s experience with that sujet, when he hired him in 1912. The bust urges us to take a closer look at the personal relationships and interactions that Mailopu experienced far away from home.

So what was Markus Mailopu's life like in Europe?

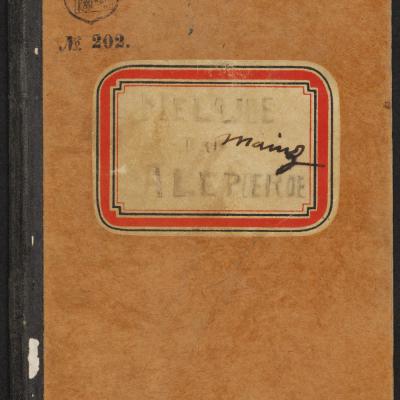

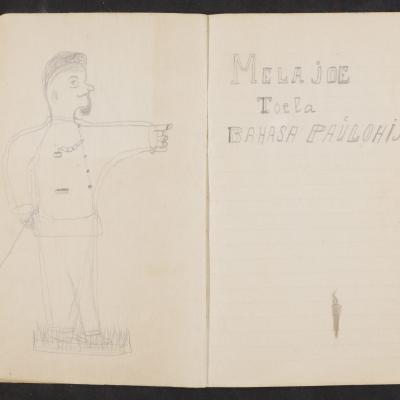

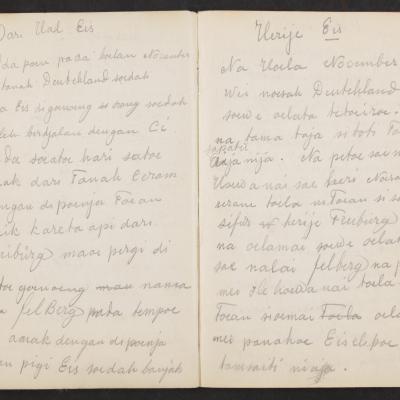

Thanks to a historical document, this question can now be explored in detail: the diaries that Mailopus compiled during his stay. These two diaries (a brown one and a black one), with a total of 110 pages, provide deep insight into Mailopus's life and experiences in Europe. Originally, Mailopu wrote the diaries for Stresemann's linguistic research, enabling Stresemann to finish his work on the Paulohi language and publish a book with the same title in 1918.4 Today, due to the dense and rich descriptions, the diaries serve as the most important contemporary accounts of Mailopu's stay in Europe.

The diaries

Mailopu’s diaries, rich in vivid detail and with recurring themes and focal points, read almost like an ethnography and offer rare insights into his life and travels in Europe. Already in the first part, which recounts the journey from Seram to Europe,5 a systematic structure becomes apparent: Mailopu notes routes, travel times, and means of transport, before turning to sensory impressions—climate, landscapes, people, and animals—often framed in comparison to Seram. The description of his later journeys within Europe follow a similar pattern.

The diary picks up seamlessly where the long journey to Europe left off, and here too, his writings focus on specific themes. As is common in a diary, Mailopu primarily reports on his everyday experiences and activities, whereby a distinction must be made here between participation in social life and the associated leisure activities, and his introduction to scientific activities. In the course of these accounts, Mailopu also explores the question—albeit only rarely—of how people reacted to his presence. Alongside this, he describes his surroundings in detail, with particular attention to changing weather and its effect on the appearance the city and nature. Another of his interests seems to have been the military, as his diaries contain repeated descriptions of military-related events. Rather atypical for a diary, but nevertheless explainable if one looks at the structure of Stresemann's diary, which may have served as a reference for Mailopu, is the recurring description of behaviors and customs that Mailopu observed. These include engagements, rituals at certain festivities, but also everyday matters such as the construction of houses. A final recurring theme in his diaries is the subject of food. After all, Mailopu had heard rumors that it was difficult to get food in Europe. However, he comes to the conclusion that this is not true, that there is a wide variety of food available and that he could eat whatever he wanted.6 Across all topics, one feature stands out: Mailopu frequently compares what he sees in Europe with his experiences in Maluku.

Traveling to and in Europe

Before taking a closer look at selected passages from the diaries, the following visualization depicts the locations where Mailopu stayed during his time in Europe. Move the cursor over the map to see the individual stops.

The content of the visualization originates from the following sources:

Riedel, Tri H., Marten, Luisa, and Markus Mailopu. Translation of Markus Mailopu's brown diary. München, 2024.

Riedel, Tri H., Marten, Luisa, and Markus Mailopu. Translation of Markus Mailopu's black diary. München, 2024.

Social life and leisure activities

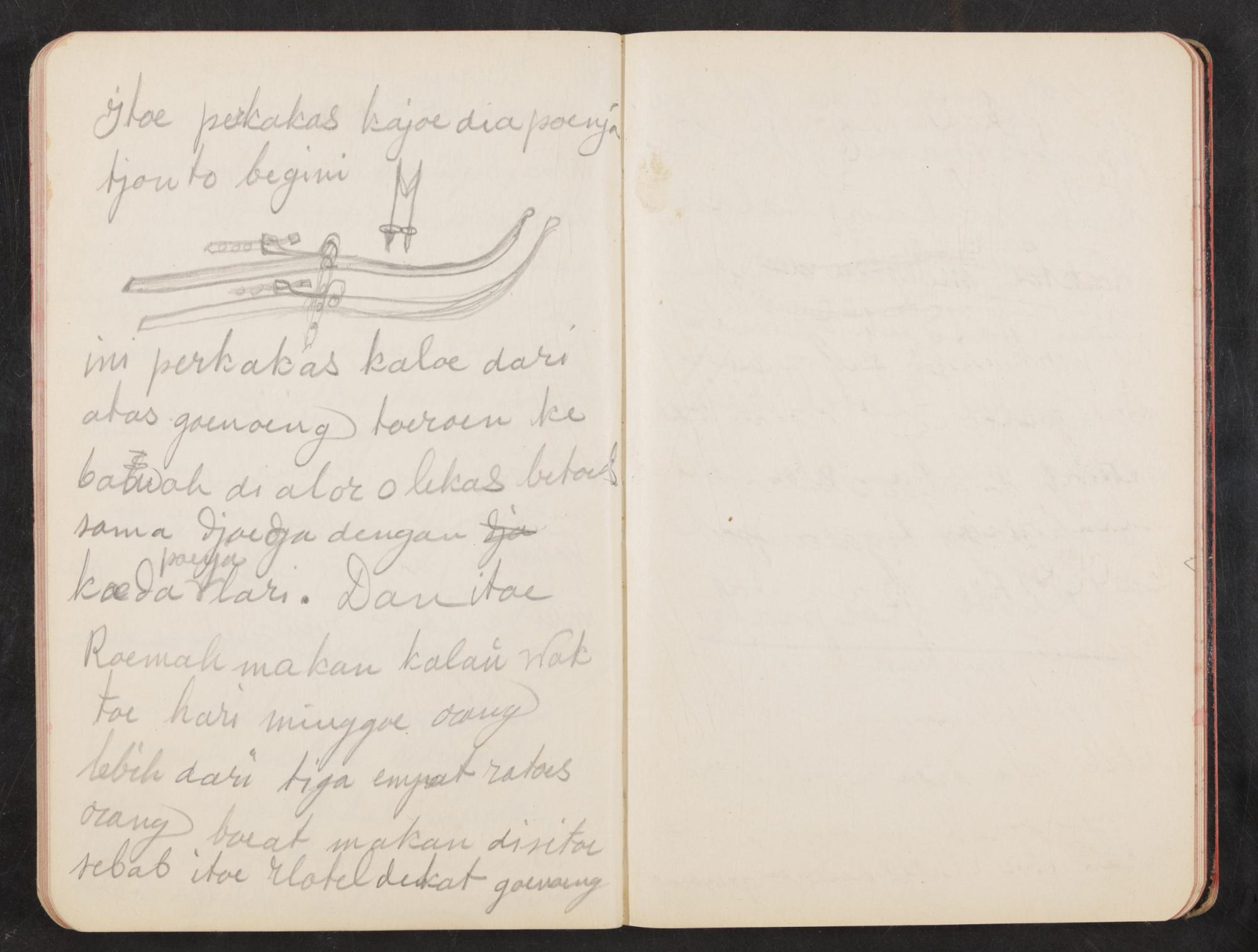

During his time in Europe, Mailopu engaged in local social life and leisure activities, as becomes evident through various of his diary entries. For instance, he describes going hiking with Stresemann and/or Deninger on Mount Herzogenhorn near Freiburg, presumably at the beginning of his stay.7 The proximity of his new hometown of Freiburg to the mountains plays a recurring role in his writings, especially because of his fascination with the snow and cold temperatures. Mailopu also recounts how he learned to ski, a popular leisure activity in the region, when the first snow fell.

At the end of their stay, Stresemann/Deninger returned to Freiburg. Mailopu, on the other hand, extended his stay on the Herzogenhorn since he had made new, academic-related contacts. During his time on the mountain, he seems to have met members of the Albingia-Schwarzwald-Zaringia student fraternity. They skied together on the Herzogenhorn, and then he took the train back to Freiburg.9

As his diary entries reveal, Mailopus's social circle soon expanded beyond Deninger and Stresemann, and he established new relationships. Mailopu's inclusion in social life is also evident in his diary entries about festive occasions such as Christmas, New Year's Eve, and Carnival. He recounts the first two experiences as follows:

In Germany, everyone puts up a Christmas tree in their homes on December 24th. The meaning of 'pohon terang' in German is Christbaum. On December 24th, Markus, Tuan Professor Dr. Deninger, Tuan Markz and 2 other Tuans were in a small house on the mountain Feldberg and we celebrated that night. We could only see snow on the left and right. We also decorated a Christmas tree in that house and we all drank wine and liquor. Jennifer ate cookies and smoked cigarettes, and sang (holy night).10

About New Year

One day in January at midnight, the situation in Freiburg was very lively. At that time, Markus prepared New Year's Eve at Tuan Rob Bornemann's house. We all drank beer and wine until twelve at midnight. At twelve o’clock everyone shouted "Prost Neujahr, Prost Neujahr" [german toast, comparable to "Happy New Year"]. Husbands kissed their wives and vice versa; and other people shook hands and wished each other a Happy New Year.11

Although Mailopu's diary primarily describes how he was positively received and included into social life, there is also an entry about his short stay in the Swiss mountains that attests to the opposite:

Introduction into scholarly activities

In Freiburg, Mailopu not only participated in social life and leisure activities, he was also introduced to scientific activities. The Institute of Geology at the University of Freiburg, where Deninger also worked, played a crucial special role in this, as this was most likely the place where he worked as a taxidermist.13 In his diary, Mailopu describes his impressions of his scientific workplace—the geological institute—in detail:

Inside the institute, various items were found from the ground, along with tools left over from ancient times. There were also sea animals such as bia raja and bia kakusang. There was kerosene available in various colors including white, red, yellow, blue, black and blue. Different types of stone were also there, for example diamond, silver, gold, copper, tin, charcoal and lime. Inside a bottle, there were octopus skin, baby octopus, octopus body and octopus bone as well. In ancient times, people used tools such as stone machetes, stone spears, stone arrows and stone hammers. In the institute, there were two people; one worked as a carpenter and the other worked as a blacksmith. The blacksmith’s task was to make hammers and repair damaged iron tools. His name was Lörge. The carpenter's job was to make hammer handles and repair broken wooden tools. The two men worked together to create the hammer sand handles. Every Tuan could take them with him if he wanted to go to the mountains. Inside the institute there were many doctors. Prof. Deeke held a high position. In his room, there was one assistant and many young Tuan and Noni-Noni students. Inside the institute, there were stones that resembled leaves and trees and the Tuans here found fish within the stones. The shape resembled sailfish and crocodiles in rocks. Inside the institute were human heads, turtle heads, lion heads, monkey heads, human bones and animal bones had been found in the ground and in rocks. Inside the institute, there were a darkroom for printing photos, a washing rooms for rocks, rooms of student Tuans as well as an exam room or a discussion room. In the discussion room, there was water, a rag, and a tool called an "Apparat". This tool was used by all the Tuans to see small objects, making them larger. In the discussion room there were only 4 Tuans.14

The description illustrates that Mailopu was familiar with the scientific surrounding, although little is known about his exact activities at the institute. It can be assumed, however, that he spent time there regularly and established contacts that impacted his personal life. After all, he celebrated New Year's Eve with Robert Bornemann, an employee from the neighboring Institute of Mineralogy.15 In addition, he seems to have been very skilled in his work as a taxidermist of geological and paleontological objects—otherwise, geologist Johannes Elbert certainly would not have gone to the trouble and expense of bringing Mailopu on another expedition.

___________________

References

- Stresemann, Erwin. Die Paulohisprache: Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Amboinischen Sprachengruppe. 's-Gravenhage: M. Nijhoff, 1918, p. v f.↩︎

- Nowak, Eugeniusz. Professor Erwin Stresemann (1889-1972) - ein Sachse, der die Vogelkunde in den Rang einer biologischen Wissenschaft erhoben hat. Hohenstein-Ernsttahl: Mitteilungen des Vereins Sächsischer Ornithologen, 2003, p. 26.↩︎

- Miehlbrandt, Sandra. "Archival Testimonies". Bilder der Natur 06/2020, Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, 2020.↩︎

-

Stresemann, Erwin. Die Paulohisprache: Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Amboinischen Sprachengruppe. 's-Gravenhage: M. Nijhoff. ↩︎

- Riedel, Tri. H., Marten, Luisa, and Markus Mailopu. Translation of Markus Mailopu's brown diary. München, 2024, p. 3.↩︎

- Riedel, Tri H., Marten, Luisa, and Markus Mailopu. Translation of Markus Mailopu's black diary. München, 2024, p. 19.↩︎

- Riedel, Tri. H., Marten, Luisa, and Markus Mailopu. Translation of Markus Mailopu's brown diary. München, 2024, p. 23-26.↩︎

- Riedel, Tri. H., Marten, Luisa, and Markus Mailopu. Translation of Markus Mailopu's black diary. München, 2024, p. 1-2.↩︎

- ibid., p. 5. About the student fraternity: In his diary, Mailopu writes "Albinggia", refering to an academic fraternity, that was founded in Freiburg in 1882. Today, the fraternity is still active as a students’ association under the name “Albingia-Schwarzwald-Zaringia”.↩︎

- ibid., p. 17-19.↩︎

- ibid., p. 20-21. Robert Bornemann was a university staff at the Institute of Mineralogy at the University of Freiburg.↩︎

- Riedel, Tri H., Marten, Luisa, and Markus Mailopu. Translation of Markus Mailopu's brown diary. München, 2024, p. 32-34. ↩︎

- This assumption is based on a letter from Johannes Elbert in which he explains to the Reichskolonialamt why Mailopu should accompany him on his expedition.↩︎

- Riedel, Tri H., Marten, Luisa, and Markus Mailopu. Translation of Markus Mailopu's black diary. München, 2024, p. 41-44.↩︎

- ibid., p. 20.↩︎