Early years in Seram

Markus Mailopu played a key role during the II. Freiburg Moluccan Expedition. Still, little is known about his life before he became part of the expedition. What we know comes from scattered references: the preface to Erwin Stresemann’s Die Paulohisprache,1 a letter from geologist Johannes Elbert,2 and most importantly Mailopu’s own diary and manuscripts, allowing us to piece together fragments of his biography.

What we know – and what we don’t know

Mailopu grew up in Ahesuru (or Makariki) at Elaputhi Bay, his mother’s home village. After the devastating earthquake of 1899, in which his aunt was among the many victims, he moved to Samasuru. Having attended a Christian missionary school,3 he was literate and mostly fluent in Malay4—skills that made him an invaluable member of the expedition. The exact circumstances of how he met the expedition members on Seram are still not known. Stresemann first mentions him in his diary on 30 November 1911, where he is described as "servant Marcus Paulohi"5. Stresemann had stopped in Sahulau a month earlier, not far from Samasuru, so it is possible that they first met there. This is one of many open questions, which we hope to find answers to in Maluku.

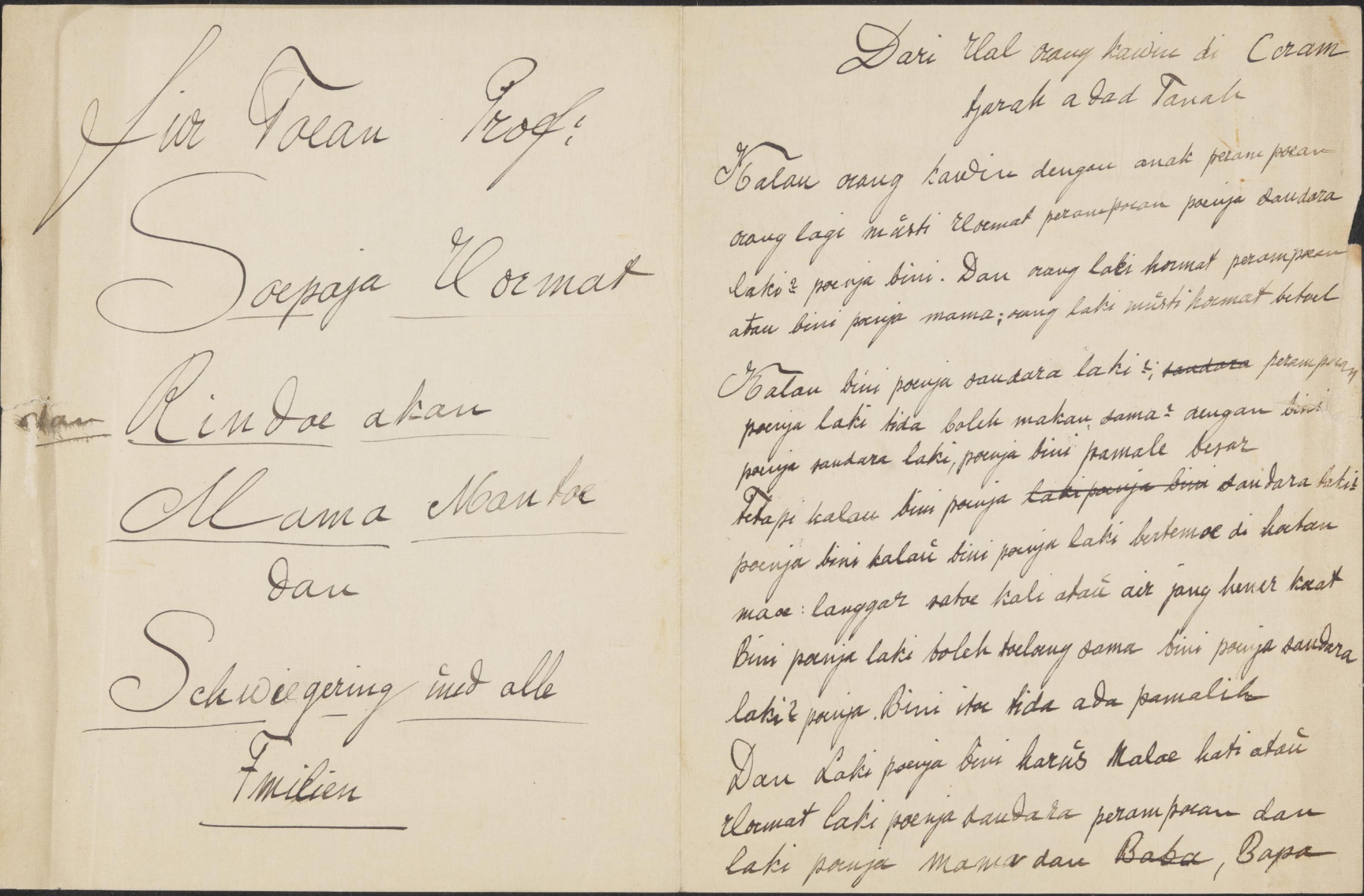

But Mailopu was certainly more than a “servant”. He shared knowledge that would otherwise have remained beyond the Expedition’s reach. In his diaries, Stresemann repeatedly mentions conversations with Mailopu about local colonial history, religion and the kakean.6 This secret men’s society fascinated European researchers precisely because most of the information remained secret. Mailopu also prepared a written account of local wedding customs, as this archival record shows.

A Witness to Disaster

Our knowledge about Mailopus’ life prior to his involvement in the II. Freiburg Moluccan Expedition is scarce. Yet, one event has been described even twice by Mailopu himself: the devastating earthquake that struck Seram on 30 September 1899, still remembered today as Bahaya Seram. In both his Paulohi manuscripts and his diary, Mailopu described what he experienced, making him an important eye witness for this catastrophic event. The earthquake struck the Elaputhi Bay area with immense force causing countless deaths. Although Mailopu provides different dates in the two sources—1899 in the Paulohi manuscripts and 1903 in the diary—the overlapping details strongly suggest both accounts refer to the well-documented earthquake in 1899. Mailopu's records provide information about the earthquake and its devastating effects on the local population. Through his writings, Mailopu offers rare insight into the destruction and human toll of the disaster. They preserve not only the memory of a natural catastrophe but also the perspective of a local witness of the time.

From Mailopu's diary

The victims suffered head injuries, broken arms, broken legs and many died at sea because they could not escape. The disaster struck a village in the Elpaputih bay. High waves surged in, causing all the residents to flee into the forest, separating them from their relatives. In that moment, many voices were heard calling out "father", "mother" and "brother".

A few moments later, the Tuans’ ship arrived. The ship was loaded with their goods such as clothes, knives, machetes, and food (tumang sago, rice and fish). Everyone ran to hide when the ship came because they were afraid of the many Dutch Tuans on board.

At that time, many doctors came to treat the victims' wounds. Many of the dead laid on the ground like useless logs. All the Tuans from the ship disembarked and buried the dead.

At that time the sea level had reached the trees on the mountain, so people could no longer escape and many of them died. From Amahei to Sahulau they no longer had the strength to withstand the natural disasters like those that occurred in Elpaputih or Paulohi and Samasuru. Both Samasuru and Paulohi sank into the sea resulting in a death toll of 2000 people. Many victims were also injured and many Alifuru people had to amputate their injured body parts to save themselves.

Everyone ran in fear to board the ship in vain when it arrived at Paulohi and Samasuru. At that time almost everyone was naked because they had no clothes.

People disembarked from the ship to bring clothes, rice, manta sago, fish, machetes, knives, and medicine for the injured. They lowered chains from the ship to disembark and then proceeded to bury human corpses.

At that time, the ship transported injured victims from Amahei, Elpaputih, Samasuru and Paulohi. There were more than 1000 injured people, so the ship could not take them all at once.

The ship returned a second time and was able to evacuate the remaining injured victims to Ambon and Saparua.7

From the Paulohi manuscript

During the night shortly before sunrise, there was an earthquake on the island of Seran. And that king and his people all died in Amahei. But on that day, all the houses in Ahesuru [=Makariki] collapsed.

And in Ahesuru there was a child named Markus. Markus was from Samasuru; his father married a woman from Ahesuru from the Soa Watimena. They lived in Ahesuru until that earthquake. And on that day, Markus' father was pounding sago on the upper reaches of the Rui River. And on that day, there was an earthquake, causing the trees on the upper reaches of that river to collapse everywhere. Markus' father and his friends fled from the village of Ahesuru that night; when they were almost within reach of the village, they waded through the water. And one said to the other: “There's nothing we can do! Our children and our wives are dead!” They waded through the water until they reached the village, where they met someone, but did not know him. And they asked him, “You! Where are the inhabitants of the village?” And he said to them, “The inhabitants of the village are all inland in Alangalang.”

And they went to the mainland and found the people of the village: One asked for his child, another for his wife and children, and a third for his mother and father; and not long after, the moon rose, and not long after that, it was morning.

And the people descended to the village and searched for clothes and boxes of clothes, and they searched for their friends, their children, their siblings. 39 people died in Ahesuru. But Samasuru and Paulohi, these two villages, sank completely.

I heard that the villages of Samasuru and Paulohi had both been drowned. And one day I left Ahesuru and went to Samasuru and Paulohi to see my father's friends; I came to the place where Paulohi and Samasuru had been, but I saw no houses and no birds, and I missed those two villages. And I stood there for a long time. Soon after, someone came from the mainland, and I approached him and asked him about my father's friends. And he said to me, “Your father's friends are all dead; but your father's sister is there in the forest with many people.”

And I said to him: “You! I don't know the way.” Then he said to me: “Let's both go!” And we both walked a short distance into the forest and found her. When my aunt saw me, she cried. The people I saw there had broken legs or arms, they had wounds on their heads and legs, and my aunt also had a wound on her leg. On the fourth day, my aunt died from that wound, and from here the people of Samasuru fled to the left toward Wae Mala; and the people of Paulohi settled in a district of the forest called Lata. Not long after, the steamer came to Paulohi and Samasuru. And the steamer dropped anchor and lay very close to the beach.

On that day when the steamer came, a man went down to the sea with a parang because he wanted to pound sago. Then that man saw the ship lying in the roadstead on the sea. And that man did not go to the sago trees, but returned from there to the group of people and said to them: “Let us flee and hide! For I saw something tremendous out there on the sea.” And the people listened to his words, and those who were healthy fled and hid, and one or two healthy men remained behind with the wounded in the forest huts.

On that day, the steamboat arrived with the Civilgezaghebber [civil governor] of Amahei. The boat unloaded the Civilgezaghebber [civil governor] and the doctor, and the Dutchmen went toward the forest and someone recognized the Civilgezaghebber [civil governor]. That person went to the Civilgezaghebber [civil governor], but he was also afraid. And the Civilgezaghebber [civil governor] asked him: “Where are the people, and where is the king?” And he said: “The king and his wife are dead!” Then the Civilgezaghebber [civil governor] said to him: “Go and call the people who have fled! The steamer will not kill them.” And he went and blew the conch shell to call all the people to come. And the Civilgezaghebber [civil governor] ordered the healthy to carry the wounded to the ship by the sea. Then the doctor applied medicine to their wounds; when the wounded saw the steamer, they cried greatly.

And on that day, over a thousand people died in Paulohi and Samasuru. The people lay scattered around like tree trunks. And on that day, so many fish died that the dogs could not eat them all. And on that day, a fish died near Ahesuru; I and the people measured it; that fish was almost two fathoms long. And I went day after day to shoot fish with my bow in a river called Nalawae, for there were many fish in it; and the fish in it had wounds on their tails and bodies, some were bleeding, some were blind. And I shot fish in that river, caught twenty of them, and returned to the forest to my father and my friends. And I took one, fried it, it was already cooked, and when I was about to eat it, my father and my friends said to me: “Don't eat that fish! For those fish have eaten the dead in the sea.” And I heard them speak thus and threw those fish away.8

___________________

References

- Stresemann, Erwin. Die Paulohisprache: Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Amboinischen Sprachengruppe. 's-Gravenhage: M. Nijhoff, 1918. (English: The Paulohi Language: A Contribution to the Knowledge of the Amboinese Language Group)↩︎

- Handwritten letter, Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv), file R 1001/3369, p. 4-6.↩︎

- ibid.↩︎

- Stresemann, Erwin. Die Paulohisprache: Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Amboinischen Sprachgruppe. s'-Gravenhage: M. Nijhoff, 1918, p. vi.↩︎

- Emge, Andus. Erwin Stresemann: Tagebücher, Berichte und Briefwechsel der II. Freiburger Molukken-Expedition 1990-1912. Singapur, Bali und die Molukkeninseln Ceram und Buru. Bonn, 2004, p. 97. (English: Erwin Stresemann: Diaries, reports, and correspondence from the Second Freiburg Moluccas Expedition, 1990–1912. Singapore, Bali, and the Moluccas islands of Ceram and Buru.)↩︎

- ibid.↩︎

- Riedel, Tri. H., Marten, Luisa, and Markus Mailopu. Translation of Markus Mailopu's black diary. München, 2024, p. 63-68.↩︎

- Stresemann, Erwin. Die Paulohisprache: Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Amboinischen Sprachengruppe. 's-Gravenhage: M. Nijhoff, 1918, p. 218-223. Original in German, translated into English by the authors. Stresemann's book contains four texts of the "Paulohi manuscript", which he transcribed, edited, translated into German and published as Paulohi speech samples in his book.↩︎